Recent developments show a pressing need to implement «digital learning and teaching» (DLT) in higher education. Research shows that DLT implementation has progressed slowly and current solutions are not well aligned with the requirements and needs of the key players [1].

Many teachers were thrown in at the deep end at the start of the pandemic with the sudden shift to online teaching activities. Everybody, regardless of attitude and previous experience had to adopt to on-line teaching in one form or another. To feel the pulse and to capture early experiences with teaching in the pandemic, we conducted interviews at the Swiss medical faculties [2]. The first reported experiences were interesting and also encouraging, as also new insights came to the surface:

«I mean, for years we have been talking about digital teaching, now we had to do it. So, it was not a bad thing…, and I hope that something remains.»

Actually, being forced into a new role imposes new insights:

«It's not about online. It's about what's your role as a teacher is. What's the role of a student? And how can you make a student learn? You need everything, you need presence, you need exchange, you need discussion. Now, we had to discuss online and offline. I don't care as long as the discussion is useful.»

Experiencing a new perspective opens up for didactic reflections, beyond that of on-line teaching.

«The role of the teacher is sometimes well off what it should be. I think the quality of teaching is actually often too low. It's not about online or not - it is about Interaction. It's not about being interactive on-line only, you have to be more interactive with the students anyway.»

Students want more flexibility, more learner control [e.g. 3]. They want to flexibly manage their learning time. For that they need access to on-line learning materiels. Students gained more learner control during the pandemic, but they also lost something very important: Social interaction with peers as well as with their teachers. The literature reports students feeling left alone with the problems they face [4]. The limited contact to peers and teachers hinders exchange in free learning groups, it also hinders spontaneous exchange with lecturers and clinical teachers. On-line forums, rapid communication channels, chats, and video-conferencing offer a good bridge, but these means do not replace direct interaction. Besides those channels being very helpful, we have all gathered experiences that show the limits of electronic communication.

Teaching has already evolved from the onset of the pandemic until the end of 2020. Most of all, the initial interrupted clinical teaching (e.g. bedside teaching, communication trainings, clinical skills training) has mostly been resumed. The experience with on-line teaching formats grew rapidly, today much clinical teaching can take place in a hybrid format (e.g. clinical skills training in which students prepare with on-line demonstration videos before practicing onsite), some even completely online (many communication trainings at the medical faculty in Bern are completely organised with Zoom), or remained completely traditional (e.g. the clinical internship rotations in Bern, that run over a year with mostly 4-week blocks of trainings in various clinics and disciplines).

For those institutions who already had existing on-line learning materials and initiatives, some gaps in teaching were bridged immediately with established on-line learning material [5, see also links below]. However, a broad range of online learning material and online learning opportunities will have to be produced for the future. The IML pursues research which aims at establishing evidence-based principles for digitally supported medical education (see links below).

Existing frameworks: The good news is, the theoretical frameworks and the methods for online teaching and learning have been described and are existing since decades: «Flipped Classroom» or «Inverted Classroom» are well known approaches among educationalists, (i.e. a combination of online and onsite teaching and learning, easy description is found here. A more general concept is “Blended Learning” (i.e. a combination of on-line and onsite learning and teaching, an easy description is found here.

Before the pandemic medical teaching was deeply rooted in traditional teaching. As long as the major experience of lecturers is related to traditional teaching, it is hard to change, in this way the pandemic was and still is a chance because it forced changes and new experiences. Now we need to take action, in order to facilitate that the new normal continues to develop, instead of reverting to traditional teaching when the pandemic would allow for it.

We promote a moderate approach in which excellent learning materials supporting individual learning is offered online. Onsite teaching and learning serve consolidation and deepening of knowledge and training of skills. Finally, the real patient can never be substituted by training and learning completely supported by models and simulations. However, practical interaction and skills when interacting with patients can be enhanced when properly supported with on-line material [6].

References

- Guttormsen, S. (2020). Die Bedeutung von Präsenz in der medizinischen Lehre: Erfahrung und Forschung Hand in Hand. In Tremp, Peter; Stanisavljevic, Marija: (Digitale) Präsenz - Ein Rundumblick auf das soziale Phänomen Lehre (Invited paper). DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4291793, 49 – 53.

- Gogollari, A. and Guttormsen, S., (in preparation): Swiss medical schools’ experiences with online teaching in the Corona spring Semester 2020. The view of the curriculum managers. 2020.

- The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. 2 ed. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. 2014, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 28. (EMSA), European Medical Students’ Association, Institutional Report for COVID-19 Impact on Medical Education. 2020 https://medisep.org/mediblog-blog10.

- Bauer D.; Brem B.; Guttormsen S.; Woermann U.; Schnabel K. (2020). How COVID-19 accelerated the digitization of teaching in the medical program at the university of Bern. VSH / AEU Bulletin, Vereinigung der Schweizerischen Hochschulen, 46, 3/4, ISSN 166- 9898

- Bauer, D., Lahner, F.-M., Huwendiek, S., Schmitz, F.M., Guttormsen, S. (2020). An overview and approach to selecting appropriate patientrepresentations in teaching and summative assessment in medical education. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150: w20382. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20382

-

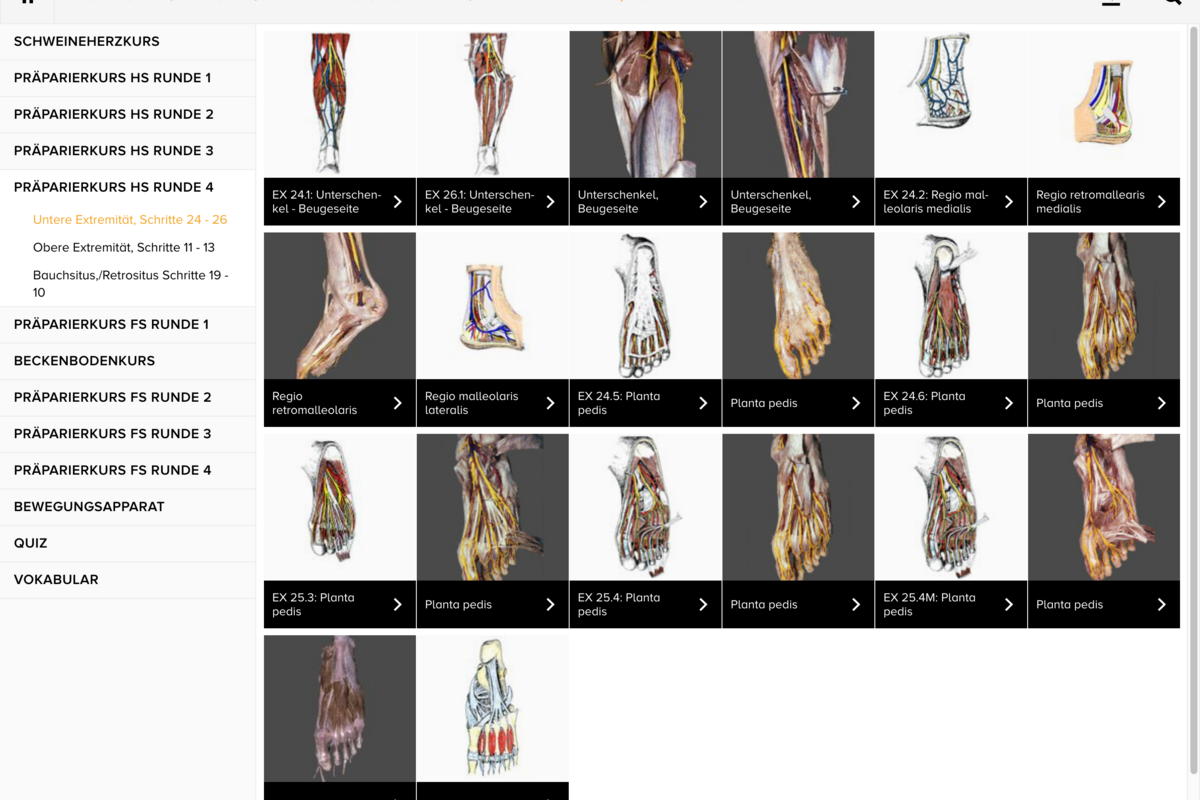

Example MorphoMed: Anatomy / Preparation training -

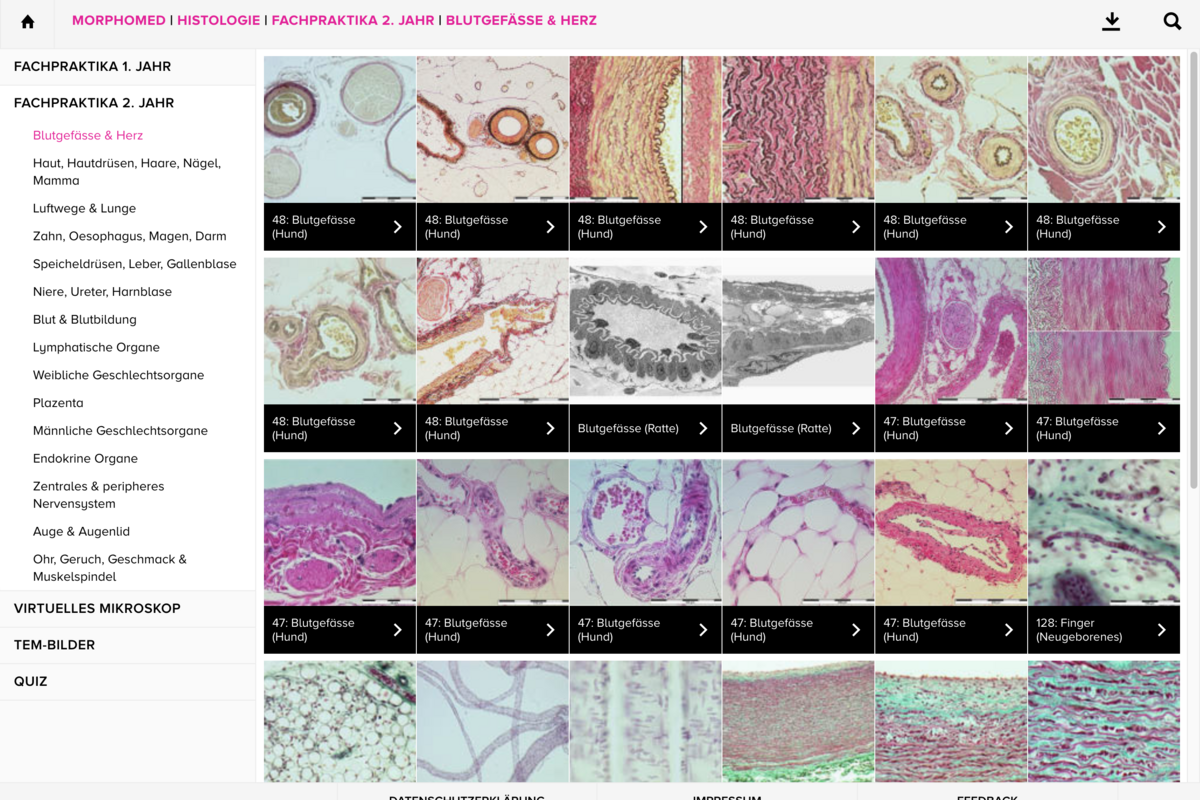

Example MorphoMed: Histology / Blood vessels and heart -

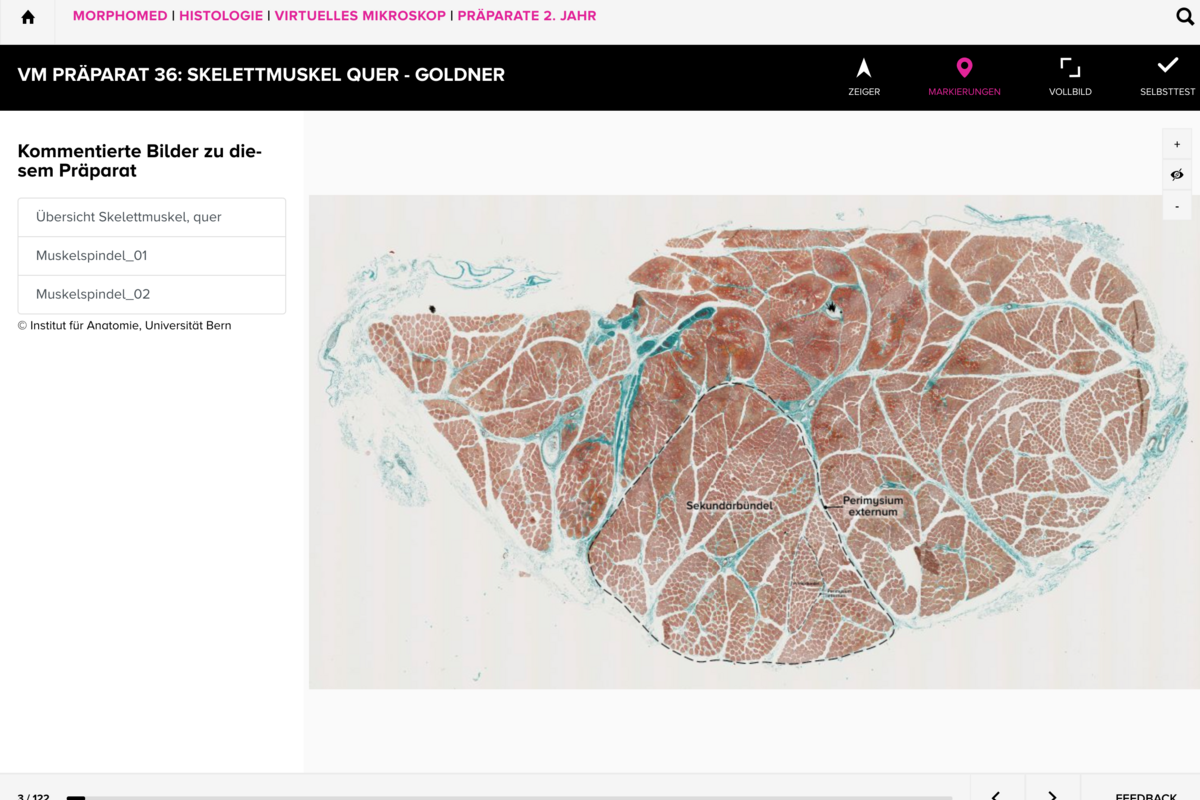

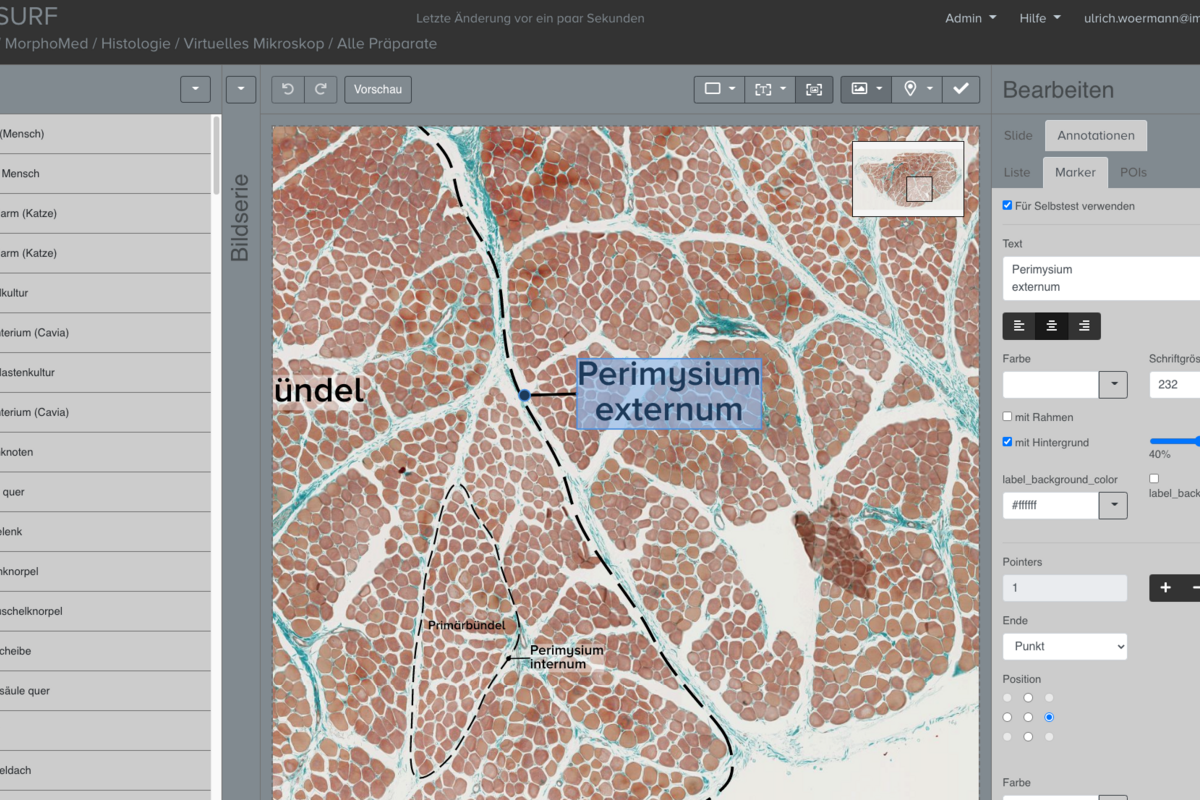

Example MorphoMed: Histology / Virtual Microscope / Skeletal muscle -

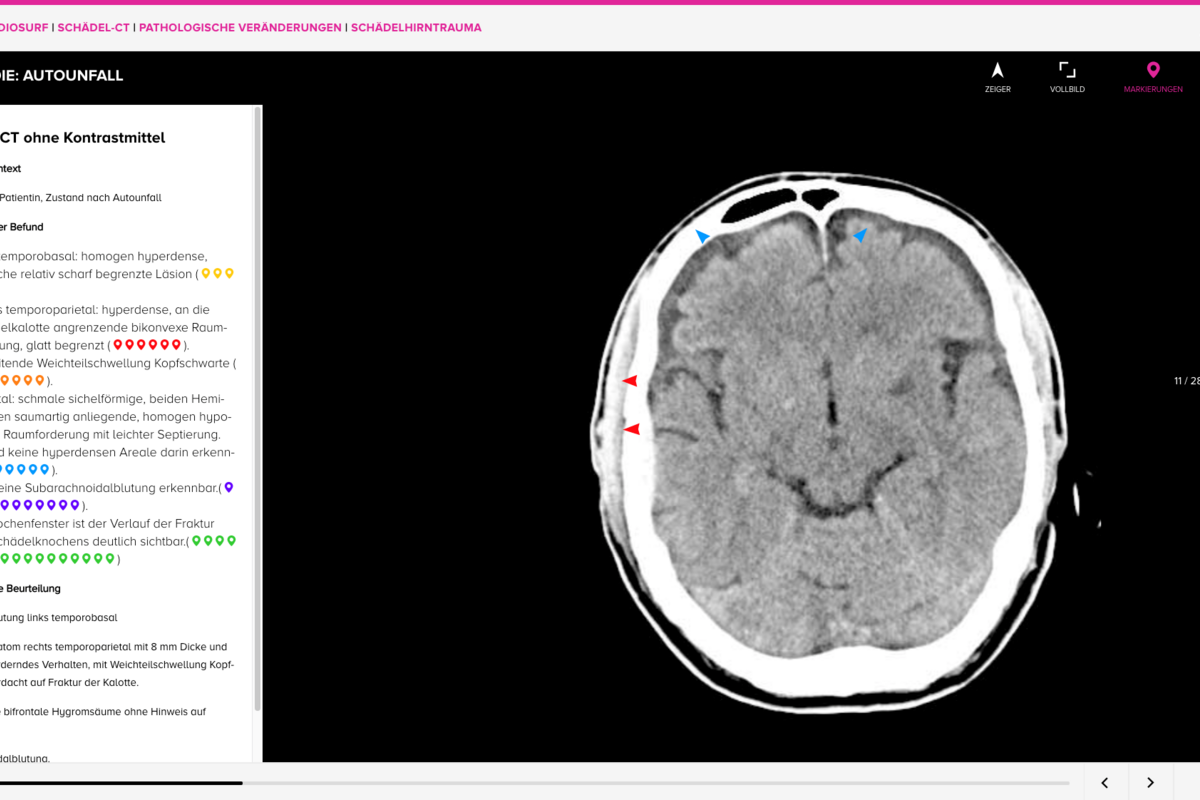

Example RadioSurf: Skull CT Scan/ Pathological alterations / Cranio-cerebral traumatism -

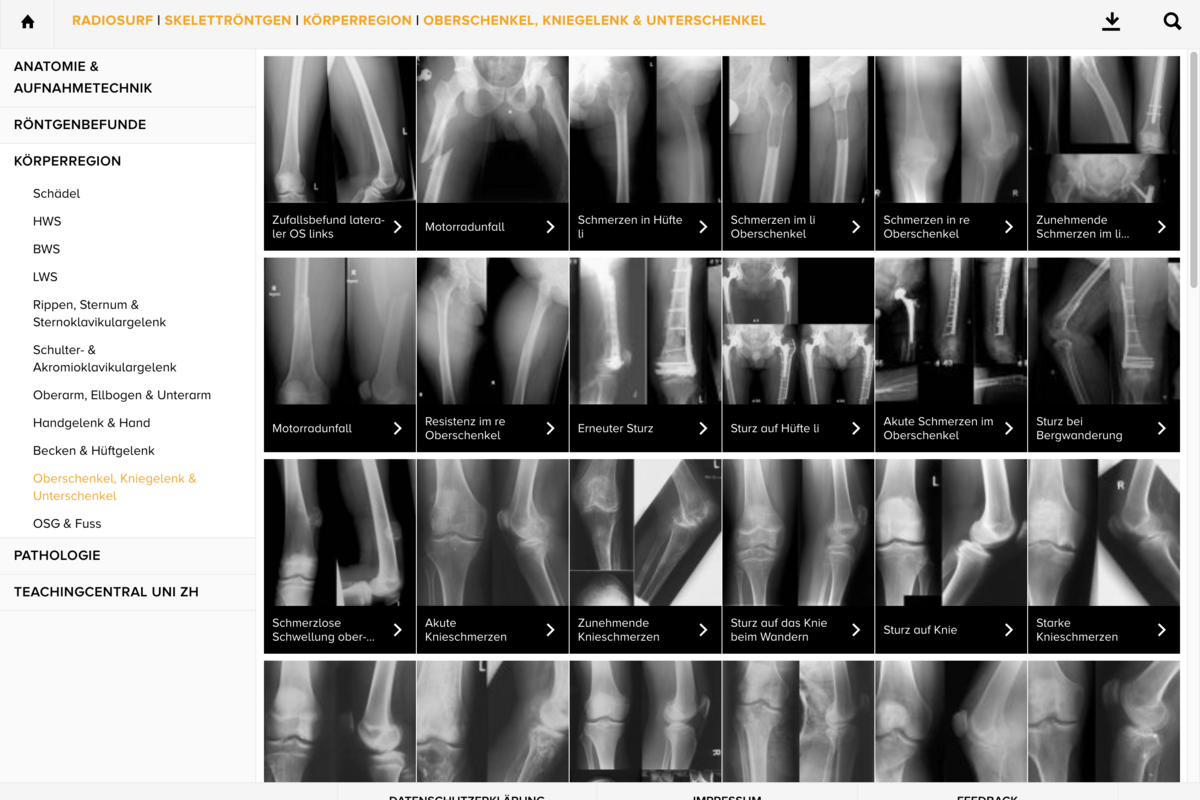

Example RadioSurf: Skeletal radiography / Knee joint and lower leg -

Example MorphoMed Authors page: Histology / Virtual Microscope